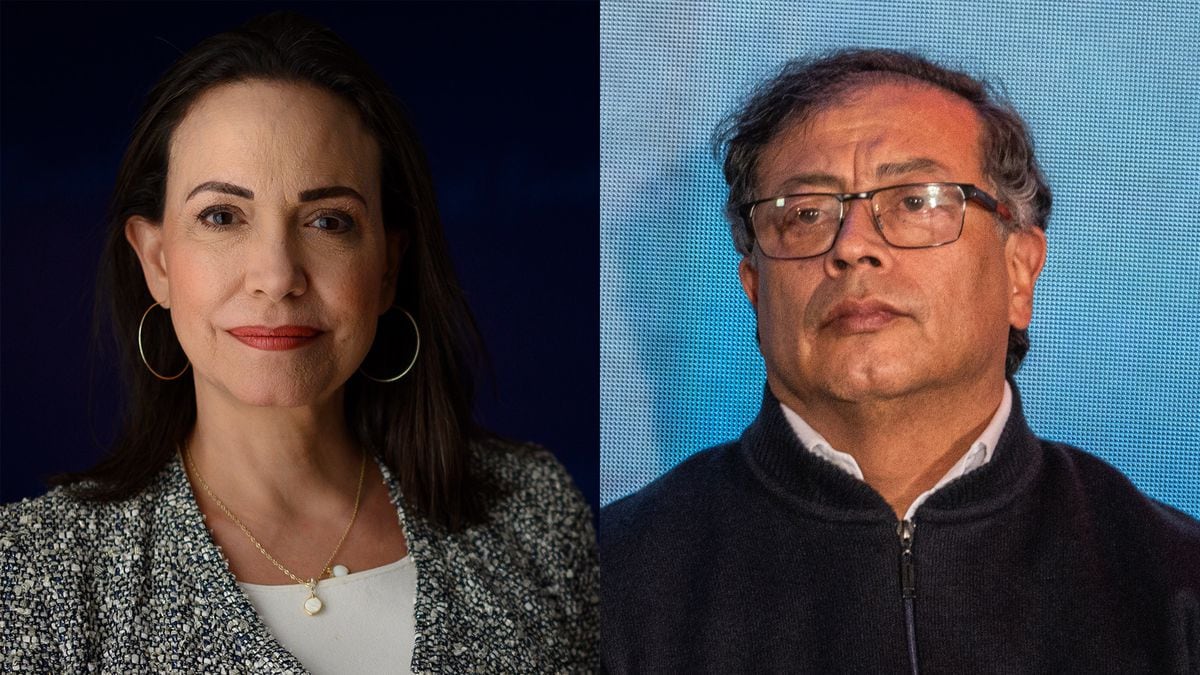

Gustavo Petro’s contradictory silence regarding the sanction against Maria Corina Machado

Pros or cons, Gustavo Petro is not a man who keeps his opinions to himself. Colombia’s president finds it difficult to remain silent. It’s hard to find an event he doesn’t talk about—national or international. Three recent examples: condemnation of Israel’s actions in Gaza, causing a diplomatic crisis; declared his support for Peronist Sergio Massa ahead of presidential elections in Argentina, marking a gap with winner Javier Milli; and supported Bernardo Arevalo to become head of state in Guatemala, judicial decisions that blocked him. Petro owes a good part of his popularity to his ability to take a stand, read situations and protest injustice. Precisely for this reason, the silence of the Venezuelan authorities against the disqualification imposed on María Corina Machado, when she wants to compete for the presidency with Nicolás Maduro, is surprising, and the Colombian president has systematically criticized the disqualification of elected officials. or candidates for office. Popularly elected positions.

The secrecy of the president is astounding. Human Rights Watch sent her a letter urging her to demonstrate against the opposition leader’s disqualification. The letter was signed by Juanita Gobertas, Americas director of the organization, who expressed her concern to EL PAÍS about the silence of the Casa de Nariño. “It is strange that he chooses to remain silent on this issue because, moreover, he has a tough relationship with him (Petro). This is allowed for a person who aspires to public office, similar to what happened to him. I believe it sends a message of inconsistency in the defense of human rights. He was furious with the dismissal of Pedro Castillo in Peru, and on the contrary, he has remained silent at the moment, as if ideological choices took precedence over his commitment to the defense of the right to vote and participate,” he pointed out by phone..

Gobertus is referring to the 14-year disqualification and dismissal that the Attorney General’s Office imposed on Petro in 2013, when he was mayor of Bogotá. A precautionary move by the Inter-American Commission returned it to the city government, and in a 2020 ruling by the Inter-American Court, it ordered the Colombian state to change its law so that no executive authority could remove an official elected by popular vote. Office.. Paradoxically, the Inter-American Court based itself on the case of another Venezuelan dissident, Leopoldo Lopez, who was disqualified for three years in 2004 by that country’s comptroller’s office. Before the Inter-American Court ruled on his case, Petro continually referred to what Lopez had experienced to support his contention that the Attorney General’s Office had violated his political rights. “My case is like that of Leopoldo Lopez,” he said on one occasion.

Ending such restrictions is a crusade the President has undertaken. In his own country he has openly disapproved of them, even when the people affected were of the opposite ideological shores from his own. In November 2021, the Colombian Comptroller’s Office sanctioned Sergio Fajardo, in his capacity as former governor of Antioquia, as one of those responsible for failures in the Hidroituango hydroelectric project, which delayed the inauguration of the mega-project and cost 4.3 trillion pesos (over $1,000 million), according to the entity. was damaged. The sanction threatened to exclude Fajardo from the 2022 presidential election. Petro reiterated his argument to defend his opponent’s rights. “What is against Sergio Fajardo is an administrative sanction and, as ordered by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, such sanction does not constitute political incapacity,” he said.

He took a similar stance in September of last year, after the National Electoral Council canceled the candidacy of Rodolfo Hernández for governor of Santander. Hernández – Petro’s opponent in the second round of the 2022 presidential election – was subject to three disciplinary sanctions by the Attorney General’s Office and the Electoral Court decided to remove him from the election. “With the case of Rodolfo Hernández, my rival in the presidential race, the thesis of removing political rights through administrative sanctions, which is mandatory, has been revived in open defiance of the IACHR ruling,” he declared.

Newsletter

Analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia in your mailbox every week

receive

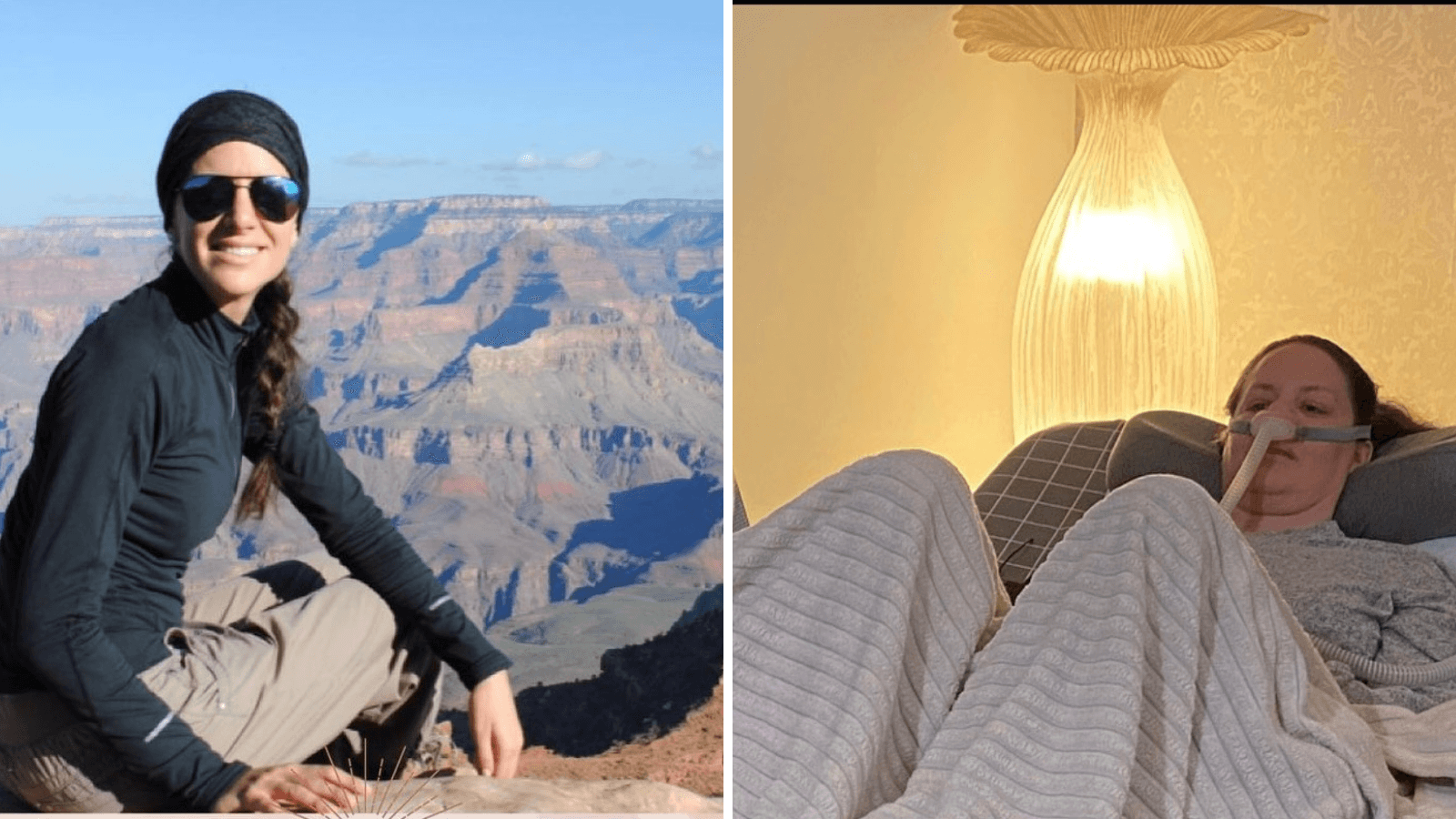

The situation is similar to that experienced by Machado, who won Venezuela’s opposition primaries in October, comfortably with 92.5% of the vote. It was a bittersweet victory. The Leader of Opposition knew she was conditioned. Four months earlier, in June, Venezuela’s Comptroller General notified him that he would not be able to run for office or hold public office for 15 years. The sentence builds on a previous sanction from 2015, when the same body disqualified her for 12 months for not including food vouchers in her asset declaration.

There was one small hope that Machado and his followers were clinging to: that Chavismo would respect the agreements reached with the opposition on the Caribbean island of Barbados and “guarantee the right of every political actor to choose his candidate for election.” Presidential election. freely.” But that was a fantasy. The Supreme Court upheld the Comptroller’s Office decision on January 26, shutting down the 56-year-old industrial engineer’s chances of appearing on the card. The United States quickly warned that if the regime did not reverse the disqualification, it would will reintroduce economic sanctions lifted months ago.With a warning, threatening tone, there is little chance of shaking any fiber in the government, which celebrates a quarter of a century in power this Thursday.

Much of the international community has turned to rejecting Chavista abuses of power. However, Petro has chosen to remain silent. He mentioned the issue only when he was through his X account in June last year. On that occasion, without directly mentioning Machado, he said that no administrative authority should “take away political rights from any citizen.” It was. By then the primaries had not been held and dialogue was underway between the ruling party and the Venezuelan opposition.

Getting opponents out of the way is a frequent weapon of Chavismo. Since 2002, the Access to Justice organization has counted 1,400 citizens ineligible to hold public office by decisions of judicial and administrative authorities. Among them are Leopoldo López, former opposition presidential candidate Henrique Capriles and Machado.

The numbers are overwhelming. However, in this case Petro has things to lose if he risks equating his case with Machado’s. This is explained by Sergio Guzmán, director of the consulting firm Colombia Risk Analysis, who believes that many of the president’s priorities depend on his relationship with the Maduro government. “Maintaining the integrity of negotiations with the ELN and Nueva Marquetalia, both of which operate in Venezuela, is key to his plans to achieve complete peace. He also proposes not to explore for oil, which is why Ecopetrol has considered doing business in Venezuela and therefore the country’s regime. It would not be strategic to contradict the decisions.” He adds that Petro’s altruism is evident when he “criticizes other leftist leaders.” “Instead of being a defender of democracy, he seems like an ally of Maduro,” he points out.

The Colombian president did not hesitate to condemn Israel. His conviction to defend his principles, even if this led to undesirable consequences, was admired by his followers, including abroad. That consistency is being called into question with his silence on Maria Corina Machado’s disqualification.

Subscribe here EL PAÍS newsletter about Colombia and Here on the channel on WhatsAppAnd get all information keys on current events in the country.

(TagsToTranslate)Colombia

Source link