The James Webb Telescope sheds light on the origin of water on Earth

The sharp eyes of the James Webb Space Telescope have once again revealed fascinating events at the heart of the formation process of a solar system like ours. An international team has just revealed an unmistakable piece of machinery, a very early and very large-scale water cycle that may better explain the origins of our planet’s water. Observations show that water ice is being destroyed and then reformed at an insane rate, equivalent to the disappearance of Earth’s oceans every month.

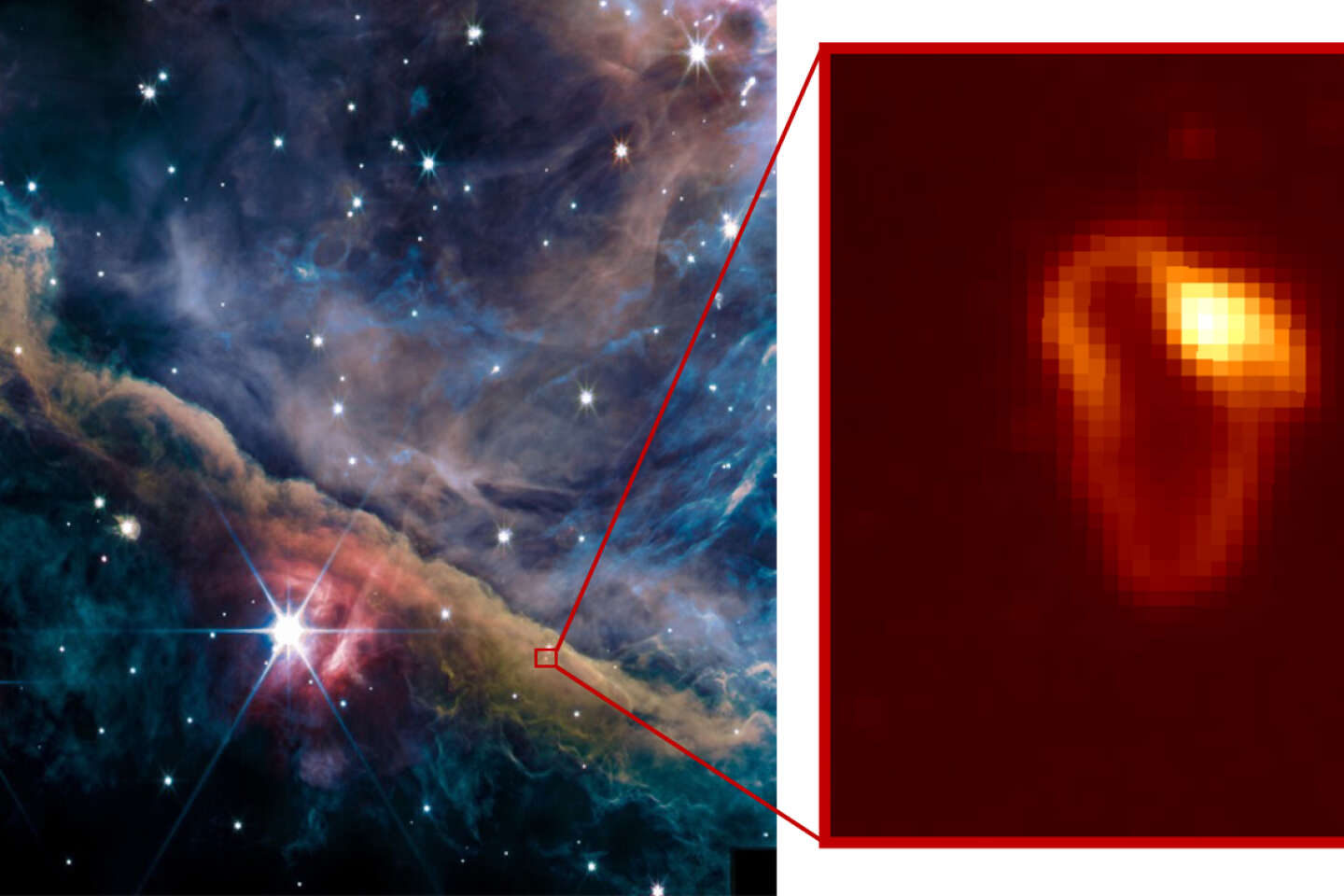

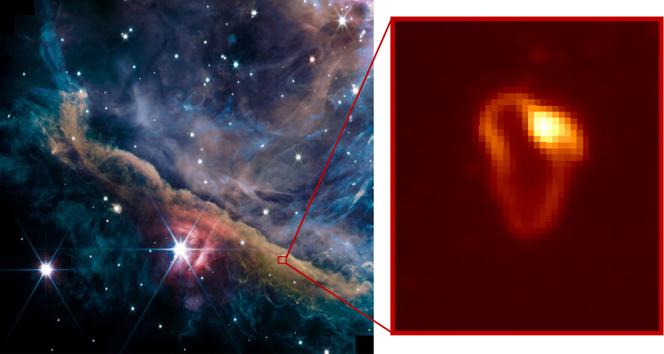

Of course, this does not happen in our solar system today, but in very young systems, called protoplanetary, one to three million years after the formation of the central star, and before the appearance of telluric planets. More specifically, the events take place within the d203-506 disk, already observed by the Hubble Space Telescope, located in the Orion Nebula, about 1,000 light-years away, our closest star nursery.

But the main details have been disclosed in an article by Nature Astronomy On February 23, James escaped Webb’s predecessor.

One molecule, two forms

These details are chemical, and also quantum. A molecule, the hydroxyl free radical, composed of an oxygen atom and a hydrogen (OH) atom, was first detected 100 astronomical units (i.e., still less than three times the mass) very close to the central star. distance between Earth and Neptune), is made up of gas and dust. and OH was in two forms. First, as if it were spinning at great speed, almost to the point of breaking. “He’s dizzy”, excites Benoit Tabon, one of the main authors of the article at the Institute of Space Astrophysics (IAS) and CNRS, who specifies that it will be equivalent to hot gas at more than 40 000 degrees (when ambient). already hot, 10,000 degrees). The second form is the vibration of two atoms, hydrogen and oxygen, that come together and move away with lower energy.

Telescope cameras that disperse, like spectroscopes, are able to detect light and, above all, distinguish these two forms of hydroxyl radicals of different energies. “It wasn’t easy, because these were very weak signals, which we weren’t sure we could “pick out” from the sound of the instrument., testifies Marion Zanies, at the end of her thesis at IAS under the direction of Emily Hebert, co-pilot of this observational project. Furthermore, theorists at the University of Leiden (Netherlands), Salamanca (Spain) and the Institute of Fundamental Physics in Madrid have been able to explain the origin of these two forms through molecular dynamics calculations, using quantum physics.

You have 47.49% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.