The viruses that have colonized our genomes: friends or foes?

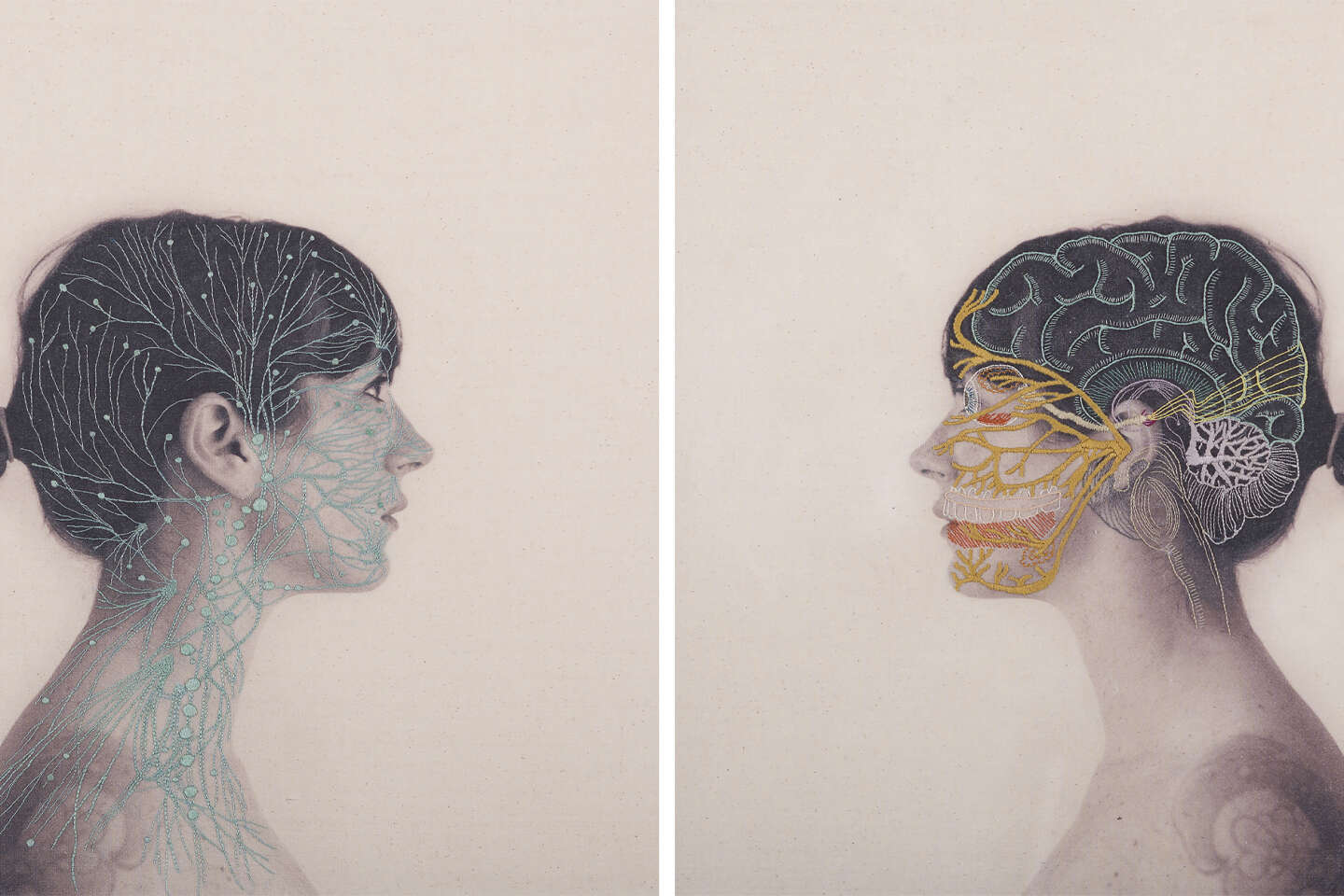

It’s just a little crazy myth like evolution, in its blind imagination, knows how to create. A very real myth, that in the past, relates to forced attachments, between viral organisms – or related ones – and their animal hosts. In time immemorial, their gnomes intermarry. Their DNA molecules were linked together and transmitted to the descendants of these animals. Willy-nilly, they evolved together and learned to co-exist over tens of thousands of years, even tens of thousands.

In short, time to get to know each other and mutually benefit from this baroque marriage. Not without some friction. Because it happens that this connection participates in the origin of various diseases in our human cells, such as cancer or hemophilia, neurodegenerative conditions or infertility.

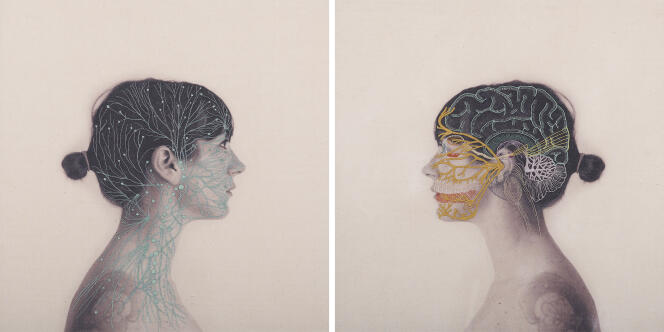

“We can only ever see one side of things; Another plunges into a night of terrifying mystery…”Victor Hugo lamented (contemplation, 1856). For a long time we wanted to see only one in our genome “Only Side of Things” : Our genes. Apparently, what mattered were the DNA sequences that delivered the instructions for making our proteins—the building blocks of our cells’ architecture and the cogs of their mechanics. But our approximately 20,000 genes, end to end, make up only 2% of our genome! Or a small piece of message engraved with this infinity ribbon.

Since then, a question has haunted geneticists. Where did all the rest of our DNA come from and what was its purpose? Stupid and trembling. Didier Trono’s team at the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland revealed on February 14 that more than 60% of our genomes come from viral entities. That’s 10% more than we thought.

“Junk DNA”

This “other side” of our DNA plunges us into an odyssey because it is unlikely. Because without these entities, which have become an integral part of our genome, we would not be here today… Rediscovering this epic story archived for 3.8 billion years in the great book of the genome. An epic as old as life.

Scientists call these organisms “transposable elements” (TEs), or “transposons.” ETs? Yes, given their unexpected origins and their astonishing ability – present or past – to survey the genome and multiply there. Fearing expansion, these globetrotters have invaded the genome, creating countless copies of themselves, capable of migrating in their stead. Hence the accumulation of repetitive DNA sequences… sometimes to the tune of thousands of copies! However, only 1% of this DNA has retained the ability to circulate in our genome; The rest are settled.

You have 83.29% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.